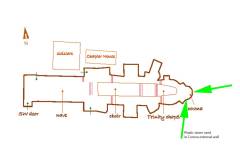

Where to see examples

Corona external wall (images 1-4 further below)

Christ Church gate (images 5-6 further below)

Description

William Caröe, the Architect to Canterbury Cathedral from 1901 to 1938, was keen to adopt the latest thinking in stone restoration and one such approach was the use of artificial stone, or plastic stone as it is often referred to in the profession. Throughout the cathedral estate during the early twentieth century minor stone repairs were carried out by infilling with mortars or stone pastes; so called plastic repairs. Plastic stone was usually made up from pieces of powdered carbonate rock bound in a lime matrix when substituting for a limestone, as at Canterbury. Caröe used plastic stone in the Great Cloister to provide a durable, inexpensive medium with a potentially good colour match with other parts of the stonework. Parts of the east face of the cloisters, for example, were refaced in plastic stone to replace the poor quality Caen stone used in the nineteenth century.

In June 1936 Caröe suspended the use of all plastic stone because of doubts he then had about the material. It was found that after a few years of exposure to the atmosphere significant colour contrasts could arise leaving the repair work to stand out like the proverbial sore thumb. At its worst plastic stone could create incompatibility problems with adjacent blocks as, whatever substitute material was used, it inevitably had a different porosity and permeability to that of the underlying natural stone. The result could be the separation of the artificial stone from the natural stone and the consequent ingress of water.

Today plastic stone is a recognised method of repairing historic buildings and its use can permit the retention of much of a building’s historic fabric. However, before being applied all arguments for and against its use have to be carefully weighed. Few examples of these less expensive remedies now survive in the cathedral fabric as most plastic repairs have been replaced, but good examples can be seen in the exterior walls of the Trinity Chapel at ground level. Other local examples can be seen on the exterior facings to the Christ Church Gateway leading into the Cathedral Precincts. Here the new ‘stone’ casing can be seen to be separating from the Kentish Ragstone beneath, but it could be argued the repairs have protected the natural stone for the best part of a century.